To Yvonne Markowitz, curator of jewelry at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, context is everything. Comment on a striking silver choker around her neck, and you learn it's one of a very limited edition created in the 1970s by Finnish artist/jeweler Björn Weckström as part of his planetary series. The kicker: it became known as the Princess Leia necklace after one was worn by Carrie Fisher in "Star Wars" as a royal, intergalactic adornment. Cool.

That kind of story is Markowitz's trademark. She doesn't just give the scholarly answer, she makes decorative arts come alive by relating them to their times. In her 20-year tenure at the MFA, much of it specializing in ancient jewelry, the Framingham resident has always focused on the big picture to draw viewers in.

Museumgoers will see her approach for themselves with the opening of the MFA's new exhibit, "Imperishable Beauty: Art Nouveau Jewelry." It's Markowitz's premier show since being named the first dedicated curator of jewelry at an art museum in the United States. To emphasize the rarity of the position, even London's famed Victoria and Albert Museum, with more than 3,500 pieces of jewelry on display, has only a part-time curator.

The position was funded by MFA trustee Susan B. Kaplan through an endowment in honor of her mother, Rita J. Kaplan. Kaplan is also funding a permanent jewelry gallery at the MFA, which will open in the West Wing in 2010.

Early in the planning stages, Kaplan met with Markowitz. Though she was officially the MFA's curator of Egyptian and Nubian adornment, Markowitz served for 12 years as editor-in-chief of the now-defunct Jewelry: Journal of the American Society of Jewelry Historians, and remains editor of the scholarly Adornment magazine. She'd become the museum's go-to person for researching jewelry from a variety of historic periods.

"She's extremely knowledgeable - that's an understatement - thoroughly researches everything and is really focused on the jewelry," Kaplan says of Markowitz. In turn, Markowitz has found a kindred spirit in Kaplan. "She has a certain passion for the materials and scholarship as I do."

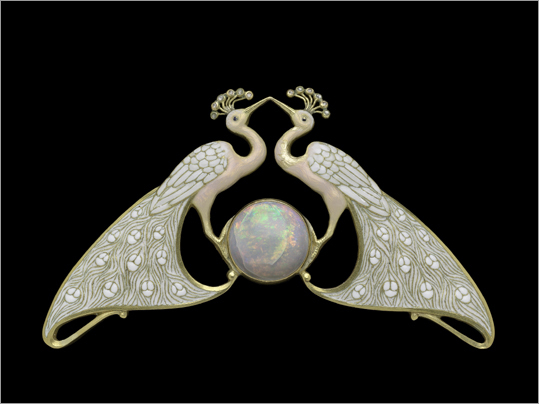

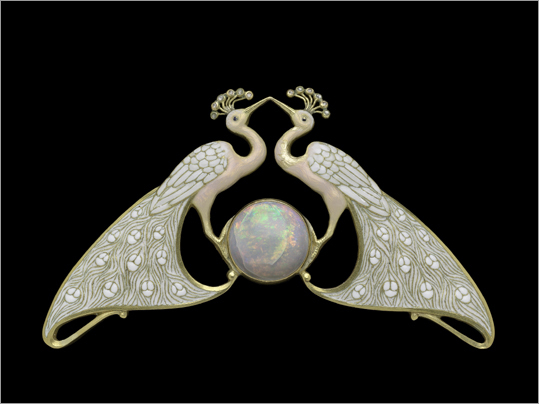

Both came into play when Markowitz began work on "Imperishable Beauty," a phrase coined by Art Nouveau architect Henry van de Velde to describe the turn of the 20th century art movement that rejected Victorian traditionalism. Markowitz describes the period's jewelry as "somewhat violent, with agitated curves," an often surreal exploration of flora, fauna, and the female form.

The 100-plus pieces in the show are on loan from one of the largest and most important private collections of Art Nouveau jewelry. The exhibit showcases the stunningly crafted jewels amid paintings, wallpaper patterns, and other decorative arts of the period. Even the walls and display cases play a part, echoing Art Nouveau's signature undulating curves.

"The problem with jewelry shows in the United States is they're segregated, not shown as part of a period," she continues, a situation she plans to correct.

Take a recent addition to the MFA's collection that Markowitz shepherded through the acquisition process. The fascinating history of an exquisite brooch and earring set once owned by Mary Todd Lincoln was equal to its beauty. As the widow of President Abraham Lincoln, she had been forced to sell the jewels, along with many other possessions, in 1867 to pay off mounting debts. Since Mrs. Lincoln's profligate spending habits were well known, the auction engendered much negative publicity (described by one newspaper as "low . . . sordid . . . disgraceful"), resulting in the articles selling for far less than expected. Press coverage also helped Markowitz verify the jewelry's provenance: an engraved drawing of jewels had appeared in a newspaper covering the sale.

Research into the Art Nouveau pieces proved a bit more daunting, due to the enormously complicated craftsmanship. Celebrated designers of the period, such as Rene Lalique, George Fouquet, and Louis Comfort Tiffany, didn't just create beautiful objects, they also invented entirely new techniques for making jewelry, such as adapting stained glass techniques to setting stones, and shaving horn so thin it resembles a transparent insect wing.

Then there was the basic issue of just who designed each piece, many of which are from France and Belgium. Unlike American designers, who signed each piece with a clear and relatively large inscription, the Europeans used tiny initials and a symbol, such as a sword or wolf, as their "makers' marks."

"When pressed into gold, it was often a blurry lump only 1/2 mm in size," says MFA curatorial research fellow Susan Ward, who worked on the exhibit with Markowitz. "We were using microscopes over three different magnifiers. I would say, does that look like a wolf to you? How about a chicken? At the end of the day, we started hallucinating," she jokes.

"We learned a lot," says Markowitz. "The museum didn't have one piece of Art Nouveau before." Happily, several items in the exhibit have been donated to the MFA's steadily growing cache, which now also includes the knockout Daphne Farago collection of 20th-century jewelry that drew large crowds when displayed earlier this year.

Another coup is the recent acquisition of an eye-popping emerald brooch formerly owned by cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post.

"I'm very fond of Post, her style and taste," says Markowitz. She then fantasizes about a future exhibit featuring some of Post's jewels - along with some of the heiress's clothing, photographs, and portraits for context, of course.

MFA jewelry curator Yvonne Markowitz holds a brooch once owned by cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post

Source: boston

Companies such as jeweler

Companies such as jeweler  Sullivan's ruling came in response to a lawsuit filed in 2004, in which Tiffany alleged that most items listed on eBay as genuine Tiffany products were fakes. The company said it had asked eBay to remove counterfeit listings, but the sales continued.

Sullivan's ruling came in response to a lawsuit filed in 2004, in which Tiffany alleged that most items listed on eBay as genuine Tiffany products were fakes. The company said it had asked eBay to remove counterfeit listings, but the sales continued.

Rio Tinto Diamonds new material positions champagne diamond jewelry firmly with those consumers who like to express their individuality and appreciate the finer things in life, the company said in a statement. The brochure, sales training program,

Rio Tinto Diamonds new material positions champagne diamond jewelry firmly with those consumers who like to express their individuality and appreciate the finer things in life, the company said in a statement. The brochure, sales training program,  "These diamonds mix and match perfectly, not only with each other but also with other colored diamonds, pearls and a variety of gemstones," said Swiss jewelry designer Suzanne Syz.

"These diamonds mix and match perfectly, not only with each other but also with other colored diamonds, pearls and a variety of gemstones," said Swiss jewelry designer Suzanne Syz.